Последние статьи

Что такое котировка

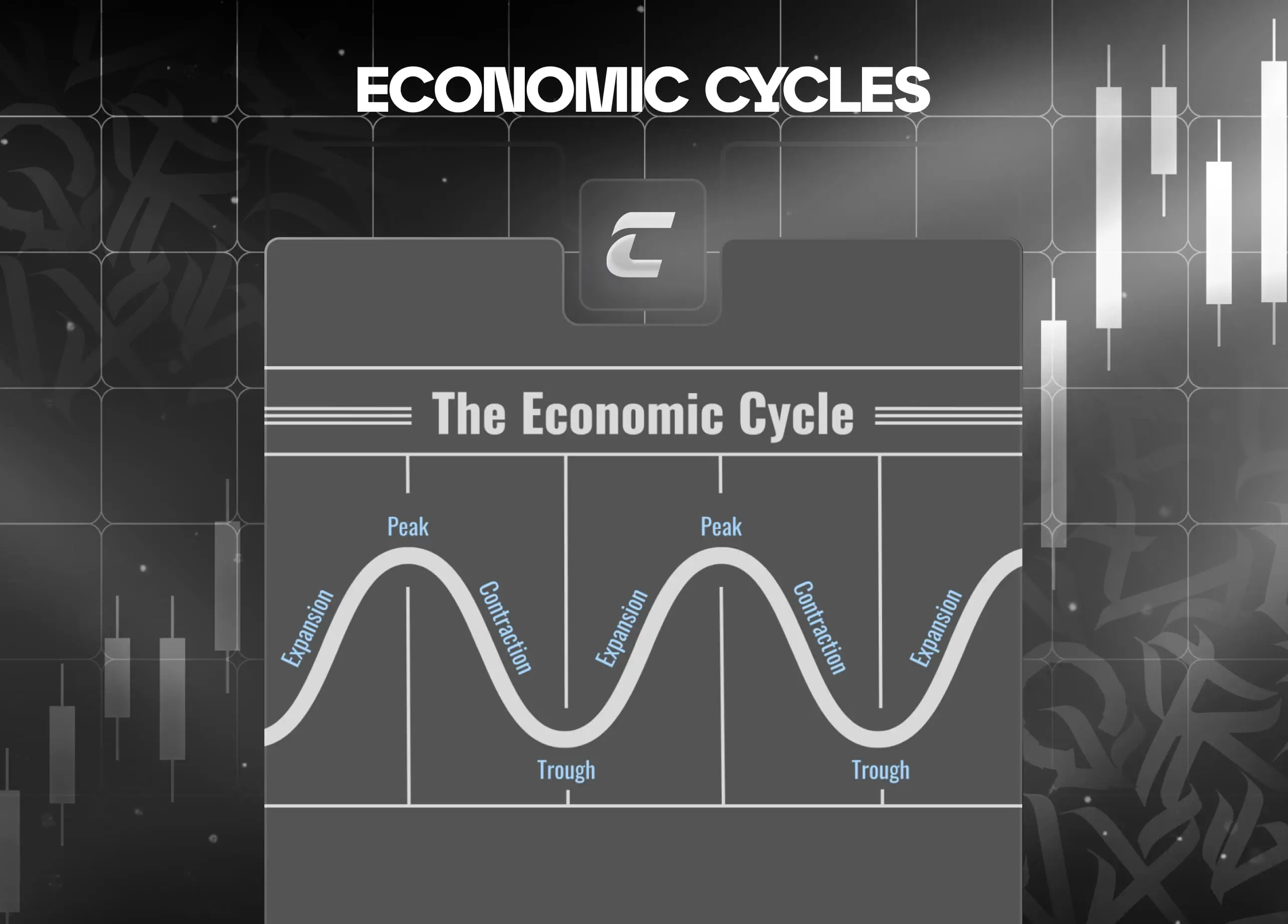

Что такое экономические циклы: фаза роста, пика, спада и восстановления

Как бороться с тревожностью во время открытой позиции

Ожидание быстрого результата: главный враг трейдера-новичка

Как пережить затяжную серию убыточных сделок

Отзыв студента: Сергей об обучении в Cryptology Key

Что такое теневая экономика и почему она мешает росту страны

Как перевести биткоин на другой кошелек

С какого возраста можно заниматься криптовалютой

Разница между дефицитом и профицитом бюджета

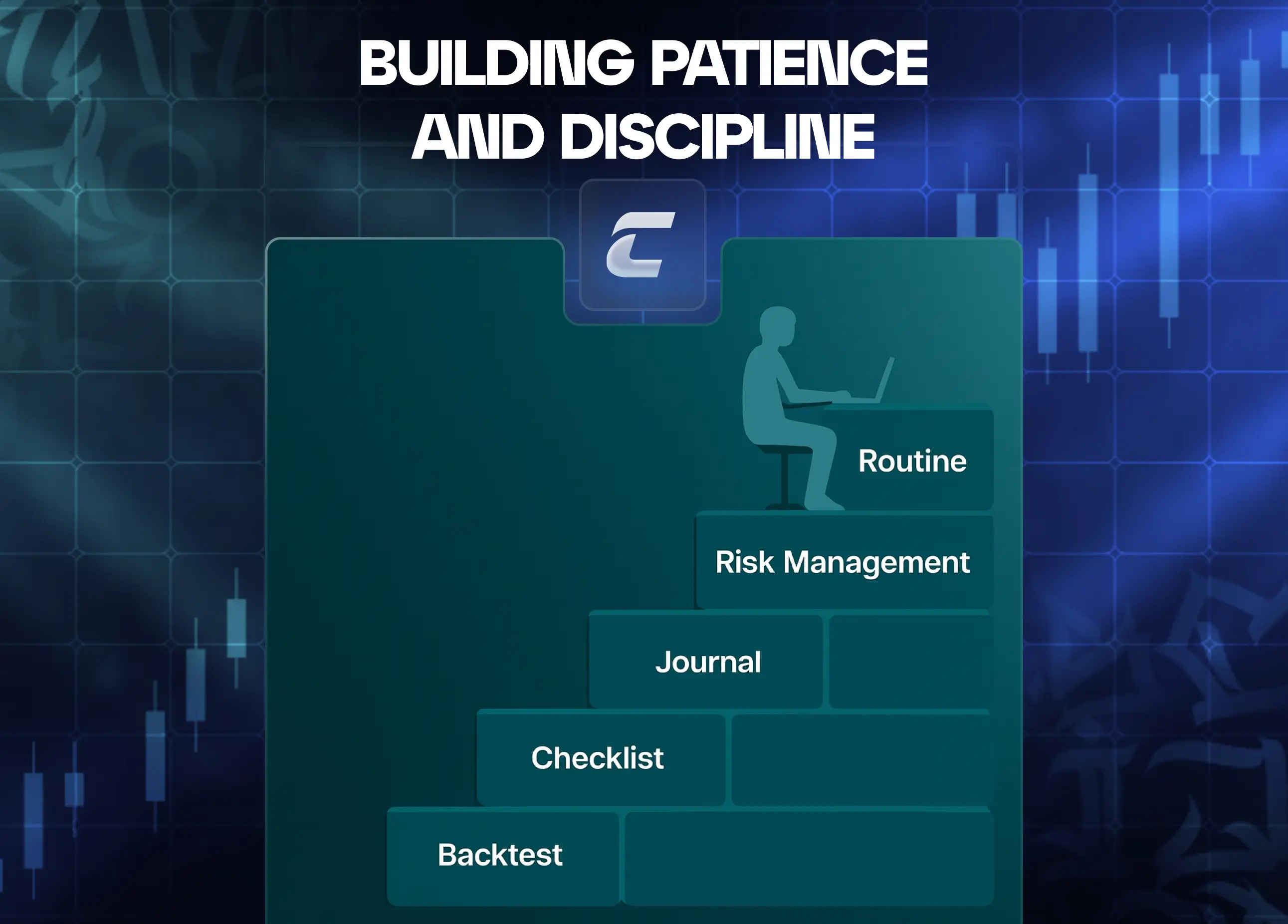

Как развить терпение и дисциплину – не на словах, а на практике

Отзыв студента: Артем об обучении в Cryptology Key